A Test of Life: Runner Rebuilding Life in Oro Valley While Fighting Doping Allegations

by Christopher C. Wuensch

11.23.05

Explorer Newspapers

It's well after sunset and the running track at Ironwood Ridge High School is pitch black, save for a magnificent strip of orange sky resisting the gathering darkness. The fading light is barely enough to reveal four lanky silhouettes circling the track so quietly their feet hardly make a sound.

Across the undulated field is Eddy Hellebuyck. His stopwatch, a permanent fixture on his wrist, gives off just enough light to reveal the intensity of his flinty face.

Hellebuyck knows dark days. The 44-year-old Belgium native has experienced them firsthand, morphing from world-class athlete and running coach into the guy on the business end of pointed fingers and quiet murmurs.

His resume is impressive: 29 marathon wins on several continents, top 10 finishes in the Boston, Chicago, New York and London marathons, four USA Track and Field Masters records and a spot on the 1996 Belgian Olympic squad.

But on January 31, 2004, none of that mattered after Hellebuyck tested positive for the performance-enhancing drug recombinant Erythropoietin, commonly referred to as r-EPO. The penalty was a two-year suspension from all USA Track and Field sanctioned events. With it came the scorn of the running world, despite steadfastly denying ever taking the endurance-building drug.

When the whispers became shouts, it was time to for Hellebuyck (pronounced Hell-a-buck) and his family to leave their home in New Mexico and head for the anonymous solitude of Oro Valley and the opportunity to start anew. "We left Albuquerque because of that," said Hellebuyck, who at the time was New Mexico's cross country high school coach of the year. "I wanted to get a fresh start, absolutely."

While the rest of the nation was grappling with the Barry Bonds vs. BALCO issue, Hellebuyck was dealing with a firestorm of his own. It culminated in his eventual firing from Albuquerque's La Cueva High School and a program he developed from ashes into a nationally-ranked cross country powerhouse. A year after Hellebuyck's departure from La Cueva, the boys cross country team slipped from No. 1 in the state to fifth, the girls from second to 10th - both with nearly the exact same team.

With a new home comes a chance for a new start for Hellebuyck and an opportunity to hone his latest passion: coaching on the international level.

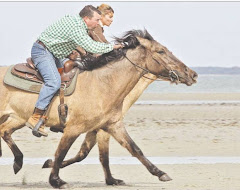

The four silhouettes gliding in the darkness of Ironwood Ridge High School belong to Samuel Githinji, Joseph Mutinda, Philip Samoei and Albert Kiplagat - a quartet of Kenyan distance runners training under Hellebuyck's tutelage.

Although his name may not resonate throughout the social consciences of the country the way Bonds' does, the Hellebuyck handle is well known in the international track and field community. He and his wife Shawn - who doubles as his agent - receive between 30 and 50 e-mails a week from runners looking to train with the former Olympic athlete.

More than 200 Kenyans are living in the United States, training and running in races. They leave Kenya for the opportunity to make money in a medium that, to them, is more livelihood than sport.

There is money to be made as a professional runner. Hellebuyck's success enabled him to retire to Oro Valley at the age of 44. As for the Kenyans, they'll earn as much money as they can before their six-month visas expire in February by running in various races throughout the country.

The winter marathon season starts in December and continues through February. During that time they'll run nearly every weekend, earning anywhere from $100 to $1,000 dollars a race. Kiplagat likely will enter the marathon season as the money leader of the quartet. Running in smaller races throughout the Southwest, he has earned roughly $7,000 in prize money to date.

There is no disposable income for these men, however. Practically every cent will return to Africa with them to support their families - and not just their immediate family. All four are running for an extensive extended family that reaches upward of 100 members.

The money is used to buy land and machines on the farms. It is not uncommon for the foursome to send money home to pay wages to the workers on their farms. Other money goes to start businesses in Kenya and to fund the education of sons, daughters, brothers and sisters.

In Kenya there is no public education. A year's worth of high school starts around $700 a year, and even with an education, a job isn't guaranteed.

Returning home with empty pockets is not an option for these men, so running the risk of doping and getting caught is a risk they say is not worth taking.

"We take advantage of the altitude and punish ourselves in training," said Githinji.

One of the only Kenyans ever to test positive for r-EPO is Bernard Lagat. The Olympic 1,500 silver medalist, who by sheer coincidence is a Tucson resident, was cleared of doping in October of 2003.

Hope of the same vindication for Hellebuyck comes from a fellow Belgian countryman.

In August, a Flemish disciplinary committee overturned a World Anti-Doping Agency charge that Belgian triathlete Rutger Beke had failed several drug screens. Beke, like Hellebuyck, also tested positive for r-EPO. Beke was able to prove, through a team of doctors, that his body produced elevated amounts of erythropoietin, or EPO. Beke's case opened a door for Spanish triathlete Virginia Berasategui to have her r-EPO ruling overturned as well.

The drug r-EPO increases the amount of red blood cells the body generates, allowing more oxygen to circulate throughout the body. More oxygen, for anyone involved in a distance sport, spells longer endurance. In higher altitudes the body naturally produces more red blood cells, the same affect of r-EPO. Hellebuyck trained in Albuquerque for several years - including at the time of the test - where the elevation is 5,300 feet above sea level. Albuquerque is the highest-elevated metropolitan city in the United States. In comparison, Oro Valley's elevation is roughly 2,600 feet above sea level.

Synthetic r-EPO is legal in prescription form and has several medicinal benefits. Doctors have used the drug to prep patients for chemotherapy and to combat AIDS. It's also believed to help reduce rejection rates in transplant patients.

Common doctor-prescribed forms of the drug are Epogen and Procrit. The drug is administered via injection and can't be taken all at one time. To properly gain all its benefits, the user must inject three times a week for several weeks. Once in the body, however, the drug only lasts around 40 hours and is gone before the effects start showing. As with any drug, there is the potential for harmful side-effects, especially when not prescribed or taken properly. Iron deficiencies are common among r-EPO abusers.

The problem with detecting r-EPO is in the test itself, which, until recently, struggled to differentiate between natural and synthetic levels of EPO.

"That was the early problem with the tests for it," said Jude McNally, Managing Director of the Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center of the University of Arizona Pharmacy Department. "When they thought about testing athletes for it, somebody convinced the world he didn't take and it showed it was still there."

Since the United States Anti-Doping Agency began testing for r-EPO in 2004, nine American athletes have been suspended for a positive test for r-EPO. Five of them, including Hellebuyck, were track and field athletes; the rest, cyclists. The native-Belgian and naturalized American has been tested six times since 2001, three of them coming in 2004, and has tested positive only once.

Hellebuyck isn't through fighting, claiming he is the victim of a false positive. He still has one more appeal to go. To assist in that battle, he's employed the same lawyer who represented Tyler Hamilton, a competitive cyclist fighting a similar r-EPO charge.

Although banned from competition by the United States Track and Field for two years - a common penalty among first time offenders - the International Association of Athletes Federation has backed Hellebuyck, which has kept his case open.

His two-year suspension will be over in January, but Hellebuyck isn't ready to give up yet.

"I have a chance that they can completely overturn it," said Hellebuyck. "I'm going to be suspended until January 31st anyway, but at least it's going to clear my name. That's the big thing."

Hellebuyck's oldest son is a freshman at Fort Lewis College in Durango and will be transferring to Pima Community College and then to the UA where he will run on the Wildcat cross country team. His younger son, Jordan, 10, is a future running star. Jordan finished fourth among all ages in the 5K at the Nov. 6 Everybody Runs event in Tucson.

Hellebuyck doesn't want the stigma of "cheater" to follow his sons through life the way it has him for the last two years.

"I don't want them to always see an asterisk behind (the) Hellebuyck name," he said. "I don't want that. It's really important that we're fighting that."

A return to coaching on the high school level could prove difficult for Hellebuyck, who will turn 45 nine days before his suspension is lifted. Eventually, he would like to crack the higher levels of coaching, perhaps with the UA or PCC cross country programs.

While finding coaches is in short order around the Amphi and Marana school districts these days, prospective candidates still must undergo stringent background checks - including Class-One fingerprinting. The same process is applied to assistant coaches and even volunteers.

"Normally we wouldn't even know something like that," said Mountain View High School athletic director Susan Sloan of hiring a coach on suspension from the USATF. "But if it did come to our attention, I'm thinking we probably wouldn't choose (Hellebuyck). I don't think the schools would touch him because we are trying to get so far away from drug enhancements or even the supplements."

MUSD's hiring procedure doesn't include anything about performance steroids, but chances are, past discrepancies would be found out through a pretty powerful "grapevine," said Sloan.

Hellebuyck isn't the type of guy who will sit around and wait for the phone to ring. The next two months will be busy ones, traveling to races in Las Vegas and Los Angeles with his Kenyan prodigies. Once they have returned to Kenya, others will take their place and the learning will begin all over, and, perhaps, for Hellebuyck, a new day will dawn.

No comments:

Post a Comment